Black holes are among the most mysterious objects in the Universe. However, the astronomers had had a hard time even discovering them, and most of the scientists did not believe in the existence of them. The reason is quite simple, though: we cannot directly see black holes, as the gravity field surrounding each black hole is so intense that even light cannot escape. So how can astronomers know they are there?

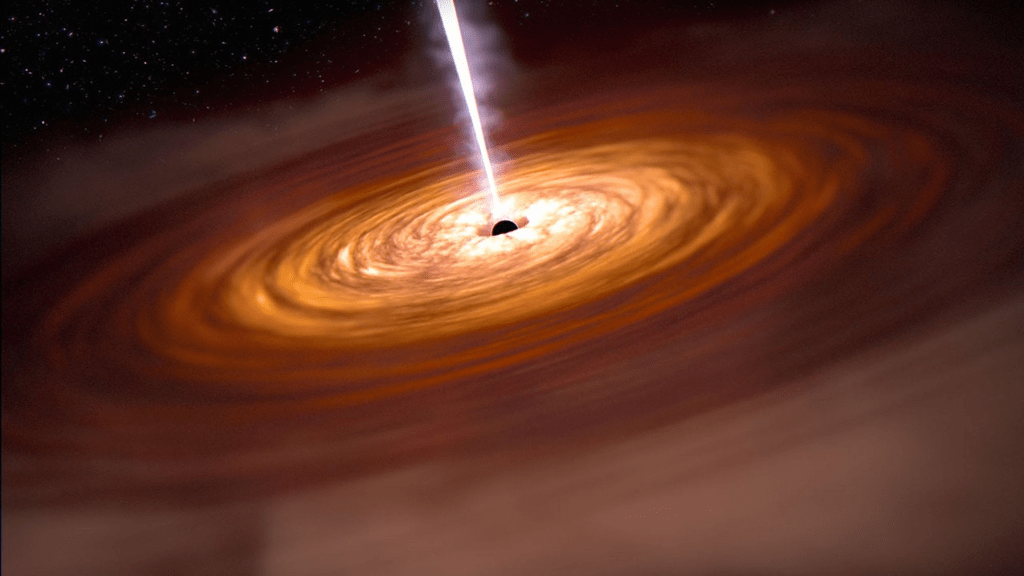

Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI).

Stellar Orbiting Unseen Objects

One of the easiest approaches for astronomers is to use Kepler’s laws to calculate the mass of the unseen object, thereby supporting its identification as a black hole.

This is the case for the discovery of Sagittarius A* – the supermassive black hole at the center of our Galaxy.

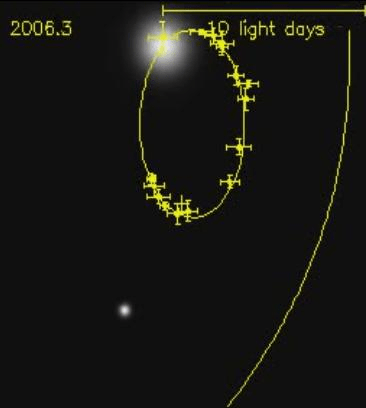

The picture shown on the right is the orbit of S2 about the Milky Way Galactic Center. From the orbit’s parameters, it can be inferred that the mass of the object is around four million the mass of the Sun, i.e. a supermassive black hole. Later, astronomers also detected relativistic effects of the orbit, therefore eliminating the possibility of being a star cluster.

Note that the largest obstacle of this approach is not about the calculations but the detection of the orbits around the black hole, as the stars are extremely faint and packed into a tiny region of sky, and the signal is constantly blurred and “shaken” by Earth’s atmosphere. In the case of Sagittarius A*, the researchers used an innovative approach, called adaptive optics, to lower the limit of angular resolution, allowing track individual stars and its full orbit.

Normally, it is difficult to draw the exact orbit of the companion star, but the line of sight (LOS) velocity is determined instead by Doppler effect. Knowing the maximum LOS velocity, the binary mass function is used to constrained the minimum mass of the other star in the binary system.

There are many variations of this approach; instead of stars orbiting the compact objects, the LOS velocity of, for example, gas particles, can also be used, as in the discovery of NGC 4258 (water masers).

X-ray Emission

In the vast universe, it is nearly impossible to pinpoint the exact location of a black hole and identify a star orbiting it; therefore, researchers first look for regions that are likely candidates to host a black hole. This is achieved by finding the X-ray emission, as the temperature of a star to have X-ray emission goes up to millions degrees.

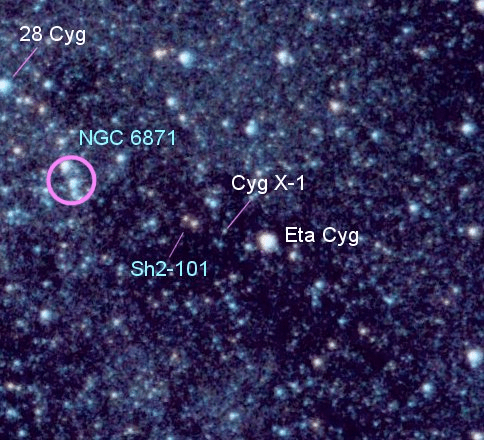

A classic example is Cygnus X-1. It was first flagged because it is one of the brightest X-ray sources in our sky, discovered during a 1964 sounding-rocket survey. The compact object is now estimated to have a mass of 21 times that of the Sun, making it a possible black hole.

Powerful Jets

As matter spirals inward through an accretion disk, it cannot simply fall straight into the black hole because angular momentum must be conserved. For accretion to proceed, the disk must transport angular momentum outward, and in many systems, a fraction of that angular momentum (and energy) is carried away by magnetically driven outflows, producing powerful, collimated jets along the black hole’s rotation axis.

In fact, the bright line in the image from the beginning of this article is the powerful jets emitting from the black hole.

Direct Imaging

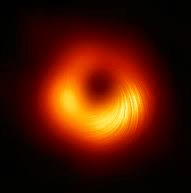

For most black holes, the event horizon is too small for the diffraction limit of a telescope (proportional to the wavelength of the light and inversely proportional to the diameter of the telescope). To tackle this problem, astronomers constructed an Earth-sized telescope by interfering the telescopes of observatories from all around the world. The famous telescope Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) based on this principle.

The picture shown on the right is the famous supermassive black hole M87* at the center of Virgo A Galaxy. Thanks to the images of the black hole, astronomers discovered a unexpected characteristic: polarization flip. The reasons behind it are still unknown.

Gravitational Waves

Years ago, gravitational waves—the “delay” in spacetime produced by accelerating massive objects—were only a theoretical prediction from Einstein’s general relativity, because the effect is extraordinarily tiny by the time it reaches Earth, making direct detection far beyond the reach of earlier instruments. However, in 2015, the LIGO detector made the first detection of gravitational waves (GW150194), proving the general relativity of Einstein and providing a new approach to determine the masses of objects.

Gravitational Lensing

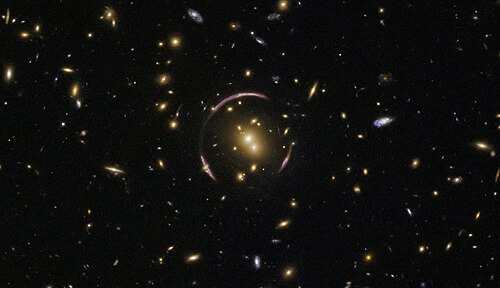

This is the phenomena when an object with large mass bends the paths of light from the star to us, making the star either distorted or be fragmented into multiple arcs – the Einstein’s rings.

Unfortunately, the Einstein’s ring is a result from a very massive object (mostly due to another galaxy); in the case of a black hole acting as a lens, microlensing will be observed: the multiple images are too close to resolve, and no single observation can establish the existence of microlensing. Instead, the source brightness will witness the rise and fall of light curve (the graph of brightness against time). From this characteristic, astronomers can calculate the mass of the gravitational lens.

Conclusion

Although the first ideas of black holes were vague and almost intangible, astronomers have spent decades turning that abstraction into evidence. By repeatedly measuring the motions of stars and gas, detecting the high-energy glow of accretion, mapping light bent by gravity, and finally “hearing” mergers through gravitational waves and even imaging horizon-scale shadows, they have confirmed that black holes are actual objects, instead of theoretical concepts.

Science is standing on the shoulders of giants.

My favorite quote, from Isaac Newton, really summarizes all the effort of the astronomers in the pursuit of discovering the myths of black holes.

However, it is just the beginning on the path of unveiling the mysteries of the Universe.

Leave a comment