Observers frequently note that the Moon appears significantly larger when situated near the horizon (at moonrise or moonset) compared to its position at the zenith (high in the sky). This phenomenon, widely observed particularly during a Full Moon, is scientifically designated as the “Moon Illusion.” Below is an analysis of the fundamental mechanisms driving this phenomenon.

The Optical Basis of Apparent Dimensions

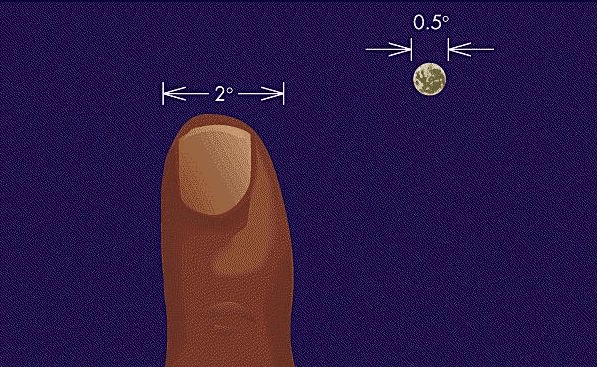

The apparent magnitude of an object is determined by two primary variables: the object’s physical dimensions and the angular diameter subtended at the observer’s eye. When observing objects of identical physical size, or the same object at different locations, the angular diameter is the determinant factor. Variations in apparent size are typically functions of distance or optical refraction.

Distance-based variation is intuitive: an object appears larger when in proximity due to a larger visual angle. The human visual system, aided by binocular vision (stereopsis) and empirical experience, is generally adept at perceiving 3-dimensional spatial depth.

A common optical effect altering apparent size is refraction. Refractive media (such as lenses, water, or the atmosphere) bend light, causing the image formed on the retina to differ from a direct line-of-sight observation. While atmospheric refraction is a real physical phenomenon, is it the cause of the giant horizon Moon?

(Note: Even a finger can obscure the Moon if placed close enough to the eye; this is simply a function of angular diameter).

Debunking the Atmospheric Refraction Hypothesis

Historically, a prevalent hypothesis suggested that the atmosphere acts as a magnifying lens for celestial bodies near the horizon. However, astronomical measurements disprove this. In reality, atmospheric refraction slightly compresses the Moon’s vertical axis (making it appear slightly oval), but it does not magnify the disk. Modern science classifies the Moon Illusion not as an optical/physical occurrence, but as a psychophysical optical illusion or a cognitive misinterpretation by the visual cortex.

Two primary hypotheses explain this psychological effect:

1. The Apparent Distance Hypothesis (Ponzo Illusion)

The Moon orbits Earth at a mean distance of roughly 384,000 km. While the orbital eccentricity causes the distance to vary (perigee vs. apogee), the resulting change in angular diameter is too subtle for the unaided eye to detect instantaneously. However, unlike terrestrial objects (houses, trees, mountains), celestial bodies lack depth cues.

This leads to a failure in depth perception. The human brain perceives the “sky dome” not as a perfect hemisphere, but as a flattened bowl where the horizon appears further away than the zenith. Because the Moon subtends the same angular diameter () at both positions, the brain applies a compensatory logic: “If the object at the horizon is further away but appears the same size as the object overhead, the horizon object must be physically larger.” This is a manifestation of the Ponzo Illusion.

When the Moon is at the zenith, the lack of reference points prevents this distance-compensation mechanism, and the brain perceives it at its “default” angular size.

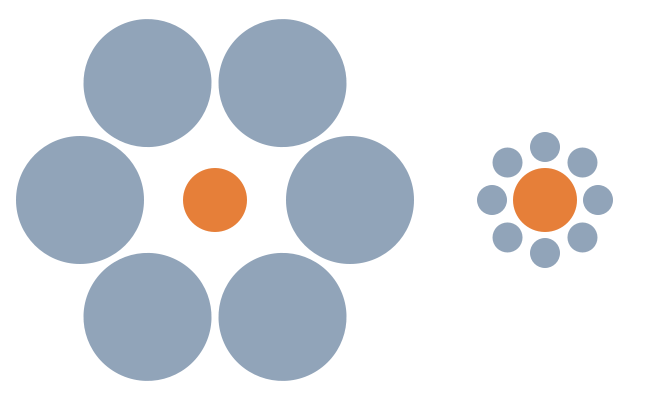

2. The Relative Size Hypothesis (Ebbinghaus Illusion)

This hypothesis posits that size perception is contextual, governed by the objects surrounding the target. This is effectively the Ebbinghaus Illusion.

- (Visual reference: The Titchener circles/Ebbinghaus illusion – where two identical circles appear different in size based on the size of surrounding circles).

When the Moon is high in the sky, it is enveloped by the vast, empty expanse of the celestial sphere. In this context of “large” empty space, the Moon is perceived as a small object.

Conversely, at the horizon, the Moon is visually juxtaposed against terrestrial reference points such as buildings, trees, or mountains. At the horizon distance, these terrestrial objects subtend very small visual angles. By comparison, the Moon appears massive.

This also explains the dramatic “giant Moon” photographs often seen in media. These images utilize telephoto compression: the photographer stands at a great distance, zooming in to magnify the background (the Moon) while the foreground objects (buildings) remain relatively small in the frame, exaggerating the scale.

Conclusion

Since the Moon Illusion is a product of visual processing and cognitive interpretation rather than physical optics, susceptibility varies among observers. Some perceive the magnification due to the apparent distance cues, others due to relative size contrast, while experienced observers who consciously override these psychological cues may perceive no difference at all.

Leave a comment