Accurate distance measurements have always been a challenge for astronomers, even for modern astronomy. In most cases, astronomers rely on the cosmic distance ladder: they estimate distances indirectly using standard candles (such as Type Ia supernovae and Cepheid variables) or galaxy scaling relations (such as the Tully–Fisher relation and surface brightness fluctuations). Yet these techniques share a fundamental limitation: their precision is constrained by calibration uncertainties and astrophysical complications, so distance estimates can carry significant systematic errors.

In the vicinity of our Solar System, distances can be pinned down by direct geometry—most famously through parallax, where a nearby star appears to shift against the background as Earth moves along its orbit. But as we push outward, that tiny angular wobble shrinks until it slips beneath the limits of even our best instruments. In other words, pure geometric distances are not something we can use freely across the universe; we get them only in rare, special circumstances. That is why galaxies with an independent geometric distance become priceless: they serve as anchors for the entire distance scale. NGC 4258 is one of those anchors.

In 1999, NGC 4258 offered astronomers a rare shortcut past the usual ladder. They watched water masers inside the galaxy’s thin, nearly Keplerian nuclear disk move in real time. VLBI mapped the maser spots on the sky, while spectroscopy captured their Doppler-shifted speeds; long-term monitoring added the slow velocity drifts (accelerations) of the systemic features. When those pieces are combined, the distance drops out of easy physics calculations. The result was a purely geometric distance of about 7.2 ± 0.3 Mpc, celebrated then as the most precise absolute extragalactic distance measured up to that point.

Initial Ideas and Discoveries

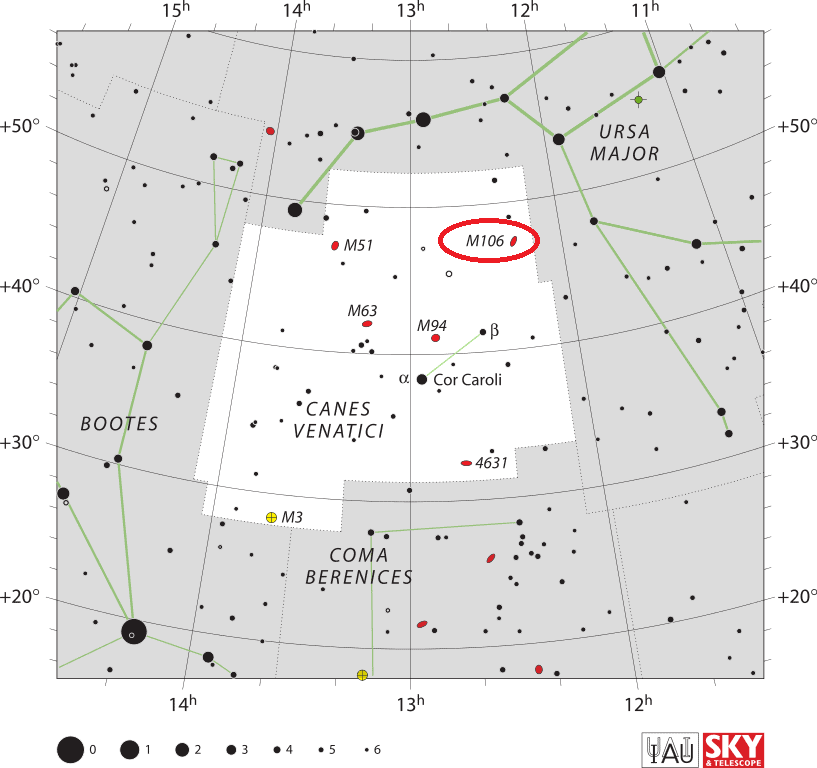

Long before astronomers began using NGC 4258 as a precision tool for distance work, it was already familiar to skywatchers as a Messier object: M106. Being one of the largest and brightest nearby galaxies, it is close enough and prominent enough to be spotted even through an amateur telescope, appearing as a soft, elongated glow under good conditions.

In 1984, astronomers detected water maser emission coming from the nucleus of NGC 4258. In this case the signal comes from water molecules emitting near 22.235 GHz, a frequency that radio astronomers can measure with extraordinary precision. At first, the detection itself was the shock: the emission was far too luminous to be explained by a single ordinary star-forming region.

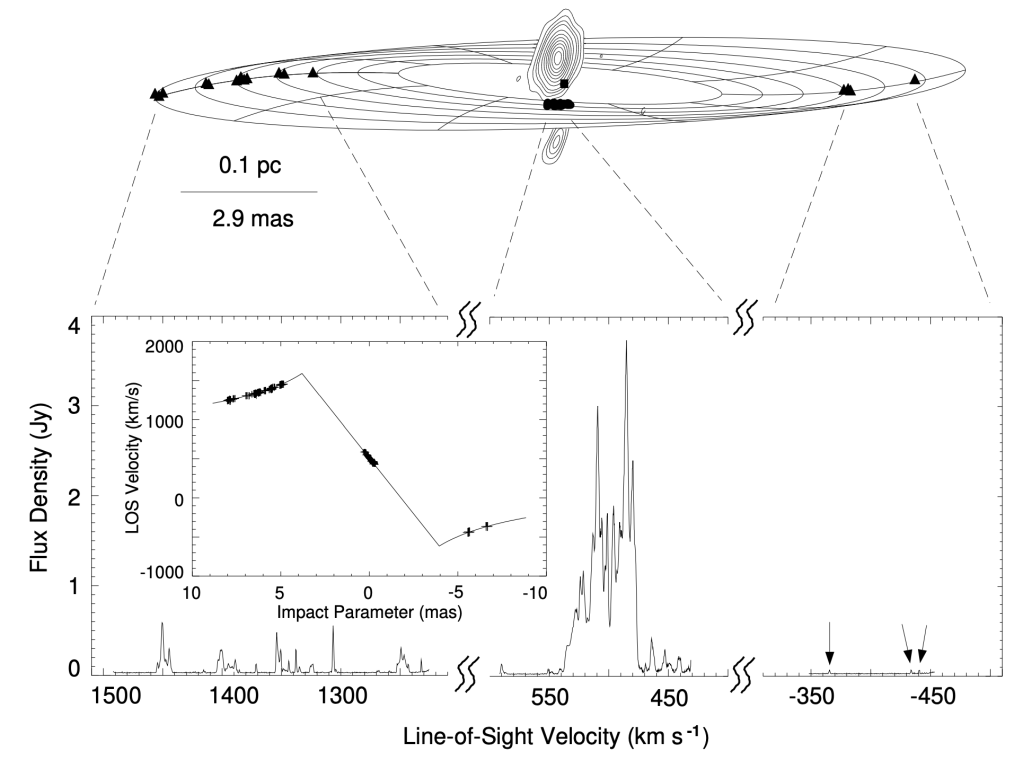

Then, a series of follow-up papers focusing on the high-velocity maser features (measured by the Doppler effect) strengthened a new interpretation: the emission was not coming from a chaotic swarm of clouds, but from a rapidly rotating, nearly edge-on disk.

The Elegant Calculations

This is, to me, one of the most beautiful calculations in the history of astronomy. From nothing more than the line-of-sight velocity astronomers could recover the disk’s true physical scale, and therefore determine the galaxy’s distance.

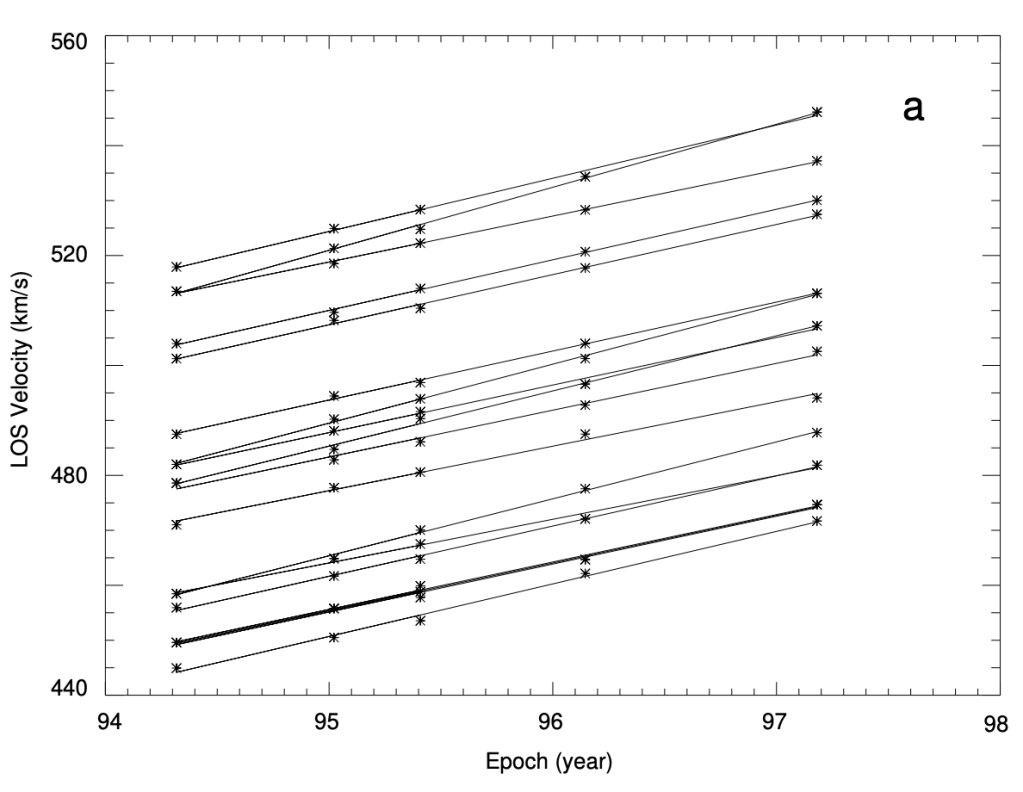

Measuring the gradual changes in Doppler velocity over time, astronomers could detect line-of-sight accelerations at different locations in the disk. In practice, the systemic masers—seen on the near side of the nearly edge-on disk—show a particularly clean, steady drift, corresponding to a characteristic acceleration of about 9 km/s/yr. Paired with a representative orbital speed of approximately 1000 km/s, (read from the high-velocity features), this immediately fixes the physical orbital radius through the circular-orbit relation:

Knowing the angular size (~2.9 mas) and the actual size (0.1 pc), it is then easy to determine the distance to this galaxy.

The Philosophy Beauty

There is a common misconception that the secrets of the universe are locked behind walls of impenetrable mathematics—that to understand a black hole, one must first master tensor calculus or general relativity. We often assume that the biggest problems require the most complex solutions.

The discovery at NGC 4258 shatters that assumption. To weigh a monster of 40 million suns and measure a distance of 23 million light-years, astronomers did not need new physics. They did not need to rewrite the laws of gravity. They simply needed clear vision and one of the most basic formulas in classical mechanics.

And this is where the true beauty of astronomy lies: not in the precision of the calculation or the formulas, but in the comprehensive picture of the Universe with roles and interplay of the objects themselves. It is the full life cycle of a star: born as a vast sphere of gas, yet dying as a gardener, enriching the cosmos with heavier elements like carbon and oxygen that catalyze the birth of the next generation of stars. It is the way gravity turns emptiness into structure, pulling faint ripples of matter into filaments and clusters, until the universe looks like a living web. It is dark matter: unseen, unlit, yet present in every rotation curve and every lensing arc, holding galaxies together like an invisible skeleton.

After all, the universe is not a cold, silent machine made of equations—it is a living narrative written in light and motion, where stars are born, burn, and return their gifts to the cosmos, and where every orbit, collision, and faint spectral line is a sentence in the same immense story.

Leave a comment