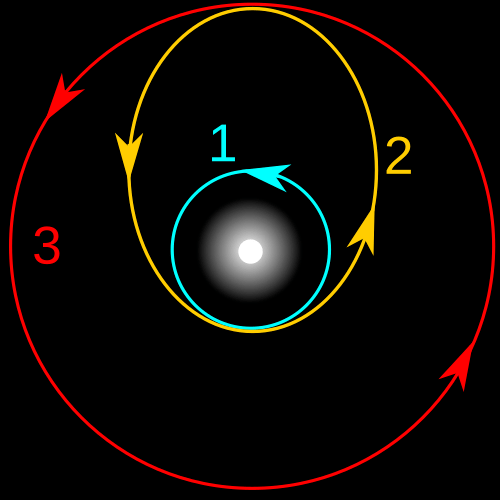

If you are a physics student, the Hohmann transfer is likely an old friend. It is the standard-issue problem for any introductory course on Classical Mechanics. You draw two concentric circles, assume a central mass, and apply the laws of Conservation of Energy.

To the student, the transfer is an elegant intellectual exercise. The logic is satisfyingly clean: you simply find the elliptical path that kisses both the departure and destination orbits. The theory proves, unequivocally, that this two-burn maneuver is the most energy-efficient way to move between two orbits. It is the geometric “path of least resistance” through the gravity well of the solar system.

But as any physics student also knows, textbook problems take place in a specific kind of universe—a universe where cows are spherical, friction doesn’t exist, and planets move in perfect circles.

The real universe is not so tidy. In the gritty reality of spaceflight, we have to deal with complex gravity perturbations, elliptical planetary orbits, launch delays, and the crushing limitations of chemical propellants.

Which leads to the question: Is the elegant geometry of the Hohmann transfer actually usable in real life? Or is it just a theoretical abstraction that falls apart when we leave the classroom?

The answer is a complicated “Yes, but…” involving patience, explosive energy, and a cosmic game of billiards. Here is the reality of the Hohmann transfer.

Hohmann transfer orbit

The first thing to understand is that for a specific slice of spaceflight, the Hohmann transfer is absolutely realistic. In fact, it is the backbone of the modern space industry.

If you look at the “local neighborhood”—Earth’s immediate vicinity and our closest planetary neighbors, Mars and Venus—the Hohmann transfer is not just a theory; it is the default setting.

The Satellite Highway Every time you watch satellite TV or check a weather forecast, you are relying on the Hohmann transfer. Most communications satellites sit in Geostationary Orbit (GEO), about 35,786 km above the equator. However, rockets don’t fly them directly there.

Instead, a rocket like the Falcon 9 or Ariane 5 drops the satellite off in a lower, elliptical orbit called a Geostationary Transfer Orbit (GTO). This ellipse is exactly one-half of a Hohmann transfer. The satellite coasts from the low drop-off point up to the high geostationary altitude. Once it reaches the top (the apogee), it fires its own onboard engine to circularize the orbit. It is a textbook maneuver executed with industrial regularity.

The same logic applies to the Red Planet. You might wonder why we don’t launch rockets to Mars whenever we feel like it. Why do we have to wait for “launch windows” that open only once every 26 months?

We wait because we are slaves to the geometry of the Hohmann transfer. We are waiting for Earth and Mars to align perfectly so that a spacecraft can slide along that fuel-efficient elliptical rail. If we tried to launch outside of that window, we would be fighting the geometry, requiring a rocket far larger than anything humanity has ever built.

For these missions, the Hohmann transfer is king. But as we look deeper into the void, the king begins to lose his crown.

Energy barrier

The realism of the Hohmann transfer collapses when we try to visit the outer solar system—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

The problem is the Tsiolkovsky Rocket Equation. In simple terms, this equation dictates that every kilogram of fuel you add to a rocket requires more fuel to lift it. This creates a vicious exponential cycle: to go just a little bit faster requires a massive increase in rocket size.

To understand why a simple Hohmann transfer to Jupiter is unrealistic, let’s look at the raw energy required. We can measure this in Kinetic Energy.

Let’s imagine we want to send a standard robotic probe (mass = 1,000 kg) from Earth to Jupiter using a classic Hohmann transfer. Earth’s Speed: We are already moving around the sun at roughly 29.78 km/s. Required Speed: To reach the height of Jupiter, our probe needs to leave Earth traveling at 38.58 km/s. This means we need to give our probe a “kick” of 8.8 km/s. That sounds fast, but let’s translate that velocity change into raw energy (Joules) and then convert that into something we can visualize: TNT. To kick a 1,000 kg probe from Earth to Jupiter using a single Hohmann burn, we need to impart an energy equivalent to detonating 72 tons of TNT directly behind the spacecraft. And that is just to get there. Once you arrive at Jupiter, you are moving much slower than the planet (because you coasted “uphill” against the sun’s gravity). To enter orbit and stay there, you would need another massive burn—another few dozen tons of TNT equivalent—to catch up. For a chemical rocket, carrying enough fuel to generate that much energy is nearly impossible. The rocket would be so heavy it couldn’t even lift itself off the launchpad.

Time limitations

If the energy requirements didn’t kill the mission, the clock would.

The fundamental rule of orbital mechanics is that there is a trade-off between energy and time. The Hohmann transfer is the path of minimum energy, which inherently means it is the path of maximum time.

For a trip to Mars, the travel time is about 9 months. This is manageable for a robot, though it is on the edge of safety for humans (due to radiation exposure).

But look at the travel times for a Hohmann transfer to the outer planets: Jupiter: 2.7 years, Saturn: 6 years, Uranus: 16 years, Neptune: 30.6 years

Imagine waiting 30 years for your probe to reach Neptune. By the time it arrived, the scientists who designed it would be retired, the computer technology would be obsolete, and the onboard batteries would likely be dead.

So, while the Hohmann transfer is “physically” possible for these planets, it is “operationally” impossible.

Other solutions

So, if we can’t power our way to the outer planets (too much fuel) and we can’t coast our way there via Hohmann transfer (too much time), how do we explore the solar system? How did Voyager 2 reach Neptune in just 12 years?

We cheated. We used Gravitational Slingshots (also known as Gravity Assists).

This technique breaks the rules of the two-body Hohmann transfer. Instead of flying a simple ellipse to the target, mission planners aim the spacecraft at a “stepping stone” planet—usually Earth, Venus, or Jupiter.

When the spacecraft flies dangerously close to the planet, it falls into the gravity well and is whipped around the back side. To the planet, nothing changes; it creates a tiny, immeasurable drag. But to the tiny spacecraft, the effect is massive. It “steals” a fraction of the planet’s orbital momentum, catapulting outward at speeds no chemical rocket could ever achieve on its own.

Voyager 2 didn’t use a Hohmann transfer to Neptune. It rode a transfer to Jupiter, used Jupiter to throw it to Saturn, used Saturn to throw it to Uranus, and finally used Uranus to throw it to Neptune.

Conclusion

So, is the Hohmann transfer realistic?

For the “inner city” of our solar system—satellites, the Moon, and Mars—it is the bedrock of spaceflight. It is the modest, reliable sedan that gets us to work every day.

But for the dark, cold reaches of the outer solar system, the Hohmann transfer is a theoretical luxury we cannot afford. The distances are too vast, and the chemical bonds of rocket fuel are too weak. Out there, we don’t rely on the gentle ellipses of Walter Hohmann; we rely on the brute force of gravity itself, swinging from planet to planet like cosmic trapeze artists.

Leave a comment